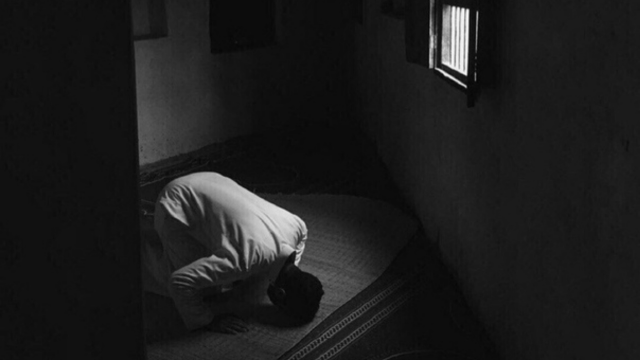

Nadia enrolled in a Higher Education institution in the Brussels region, part of the French-speaking community higher education network. She wears a headscarf and everything goes well for her at the beginning of the year within the institution. One morning, while waiting in a hallway, a member of the teaching staff approaches her and asks her to remove her headscarf and jewelry, claiming that this attire would contravene the principles of neutrality within the institution. However, she has never heard of such a ban and finds nothing explicit in the school’s regulations.

What does the law say?

The Belgian State is required, under Article 24 of the Constitution, to provide neutral education, free from any religious, philosophical, or political influence. This principle of neutrality also extends to higher education, including Colleges and Universities.

Freedom of expression, opinion, and worship are therefore guaranteed in Colleges and Universities, in accordance with the Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Students can, in theory, wear what they want, including signs of conviction such as the headscarf.

Thus, in the French Community, higher education falls within the scope of the decree of March 31, 1994, defining the neutrality of education. Article 3 of this decree states that:

” The Community school guarantees the student or the student, with regard to their degree of maturity, the right to freely express their opinion on any matter of school interest or relating to human rights. This right includes the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas by any means of the student’s choice, subject to respect for human rights, the reputation of others, national security, public order, health and public morality, as well as the internal regulations of the institution. The freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs, as well as the freedom of association and assembly, are subject to the same conditions. “

However, these freedoms are not absolute. Higher education institutions can, autonomously, restrict these rights through their internal regulations, provided that these restrictions are justified by legitimate reasons such as safety, hygiene, or neutrality. These restrictions must also respect, like any restrictions on fundamental rights, the conditions of legality, necessity, and proportionality set by law and jurisprudence.

In Belgium, the Constitutional Court issued a ruling on June 4, 2020, concerning the application of Article 3 of the decree of March 31, 1994. It was responding to a preliminary question related to the general ban on wearing signs of conviction within the Francisco Ferrer College, organized by the City of Brussels. The Court confirmed that the decree does not violate Article 19 of the Constitution and Article 9 of the ECHR and does not prohibit institutions from providing for such restrictions, but does not oblige them to do so. It also emphasized that the notion of neutrality can be defined in a flexible and evolving manner.

Furthermore, on November 24, 2021, the Court of First Instance of Brussels ruled in favor of the students and judged that the general ban of the Francisco Ferrer College constituted indirect discrimination based on religion, in violation of the decree of the French Community of December 12, 2008, relating to the fight against certain forms of discrimination.

Consequently, higher education institutions must respect the principle of neutrality provided for in Article 24 of the Constitution. However, students generally retain their freedom to wear distinctive signs, including religious signs such as the headscarf. If an institution wishes to impose a ban, it must be clearly mentioned in the internal regulations, pursue a legitimate aim, and be proportionate. A ban targeting a particular religious sign would violate the anti-discrimination laws in force.

Belgium does not have a law generalizing the ban on wearing distinctive signs within educational institutions for pupils and students. Moreover, the Council of State reminds in its decision of December 21, 2010, that the Belgian state is not strictly speaking a secular state and that the notions of secularism and neutrality are distinct.

The Belgian state must guarantee education that is neutral in terms of religious, philosophical or political beliefs under Article 24 of the Constitution, which states that “Education is free (…) The community ensures parents’ freedom of choice. The community organizes education that is neutral. Neutrality implies, in particular, respect for the philosophical, ideological or religious views of parents and students” . The objective that this article of the Constitution aims to pursue is respect for the plurality of opinions of students and parents. The freedom of parents offered by Article 24 results in communities having the obligation to establish and organize neutral public education.

There are therefore two educational networks in Belgium: education organized by the communities, which includes public institutions, and free education which consists of private institutions, certainly subsidized by the communities, but which are not organized by the latter and are free to follow a specific religious, philosophical or pedagogical approach.

As for private education in Belgium, institutions in this network are autonomous in deciding whether or not to implement restrictions on distinctive signs, provided they justify such restrictions under the anti-discrimination laws in force.

What should I do?

- Consult the internal regulations of the higher education institution

- Communicate the current legislation as well as relevant court decisions to the management.

- Initiate an internal procedure to amicably resolve any conflicts between the student and the institution.

- Appeal to student representative organizations (delegates, student unions) within the institution in question.

- Contact UNIA to report discrimination.

- Contact the CCIE’s legal department, which will support you at every stage.

Sources:

- Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

- Articles 19, 24 and 127 of the Belgian Constitution.

- Law of May 10, 2007 to combat certain forms of discrimination.

- Decree of March 31, 1994 defining the neutrality of education in the French Community.

- Special decree relating to Dutch-speaking community education of July 14, 1998.

- Decree of the French Community of December 12, 2008 on combating certain forms of discrimination.

- ECHR, November 10, 2005, Leyla Şahin v. Turkey.

- Constitutional Court, June 4, 2020, No. 81/2020, “Francisco Ferrer”

- Court of First Instance of Brussels, November 24, 2021, “Francisco Ferrer”